The MAD Origins of the Computer Age

Posted on | April 11, 2016 | No Comments

It was the “missile gap” that would impregnate Silicon Valley with the purpose and capital to grow to its famed stature as the center of computer innovation in the world. During the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, when Robert S. McNamara was Secretary of Defense, the US undertook an enormous military buildup, with the intercontinental missile as its centerpiece. The policy of “Mutually Assured Destruction” (MAD) and specifically the advancements in the Minute Man II missile led to the development and refinement of silicon integrated circuits and ultimately the microprocessor “chip.”

The computing and network revolutions were powered by successive developments in information processing capabilities that were subsidized by extensive government spending and increasingly centralized in California’s “Valley of Heart’s Delight,” later known as “Silicon Valley.”

At the center of this transformation was an innovation developed by the telecommunications monopoly, AT&T. The government-regulated monopoly developed the first transistor in the 1940s at its New Jersey-based Bell Labs. This electronic switching technology would orchestrate the amazing machinations of the 1s and Os of the emerging digital age. William Shockley, who won a Nobel-prize for the AT&T sponsored invention, soon decided to return to his California home to set up a semiconductor company.

Shockley had been recruited back to the area by Frederick Terman, the Dean of the Engineering School at Stanford University. Terman was a protégé of Vannevar Bush, the major science and technology director of the New Deal and World War II, including the Manhattan Project that invented the atomic bomb. Terman designed a program of study and research at Stanford in electronics and spearheaded the creation of Stanford Research Park that leased land to high-tech firms. In the early 1950s, Lockheed set up its missile and aerospace subsidiary in the area. IBM also set up facilities for studying data storage during that time.

Shockley’s company did not achieve the success it desired, and some of the employees left and started up companies such as Fairchild Semiconductor (Later Intel), National Semiconductor, Advanced Micro Devices, and Signetics. Luckily, history was on their side as the Sputnik satellite crisis almost immediately resulted in several government programs that targeted guidance miniaturization as a crucial component of the new rocketry programs. Transistors became the centerpiece of a set of technologies that would guide rocket-powered missiles, but also provide the processing power for modern computers.

The Minuteman intercontinental missile project was originally approved on February 27, 1958, about six weeks after Eisenhower requested funds to start ARPA. Both were in response to the previous autumn’s successful flights that delivered two USSR Sputnik satellites into space. The Soviets had captured many German V-2 rocket scientists after the World War II and quickly built up a viable space program. Meanwhile, they denoted an atomic bomb in August 1949 and in 1954 they successfully tested a hydrogen bomb, thousands of times more powerful than the atomic device. While the second of the Sputnik launches had only placed a small dog into space, the fear spread that the USSR could place a nuclear warhead on their rocket. Such a combination could rain a lethal force of radiation upon the US and its allies, killing millions within minutes.

About a year before, in late January 1957, the US had finally reached success with its own space program, using a modified Jupiter C rocket to carry the first satellite into space. Still, the 10.5-pound satellite was in no way capable of lifting the massive weight of a hydrogen warhead, not to mention guiding it to a specific target a half a world away. Sensing the momentousness of the task, Eisenhower started NASA later that year to garner additional support for the development of rocket technology by stirring the imagination of humans being launched into space.

The Minuteman was conceived as an intercontinental ballistic missile system (ICBM) capable of delivering a thermonuclear explosion thousands of miles from its origination. It was meant to be a mass-produced, quick-reacting response to the “perceived” Russia nuclear threat. Named after the American Revolutionary War’s volunteer militia who were ready to take up arms “at a minute’s notice”, the missile was a revolutionary military idea, using new advances in guidance and propulsion to deliver its deadly ordinance.

-

Eisenhower left plans for a force of about 40 Atlas missiles and six Polarises at sea; in less than a year Kennedy and McNamara planned 1,900 missiles, consisting primarily of the 1,200 Minuteman missiles and 656 Polarises. Counting the bombers, the United States would have 3,455 warheads ready to fire on the Soviet Union by 1967, according to McNamara’s secret Draft Presidential Memorandum on strategic forces of September.[2]

McNamara was an intense intellectual and considered one of the “Whiz Kids” brought in by Kennedy as part of the promise of the new administration to recruit the “best and the brightest.” He was extremely good with statistics and steeped in management accounting at Harvard. During World War II, he left a position at Harvard to work in the Statistical Control Office of the Army Air Corps where he successfully planned bombing raids with mathematical techniques used in operations research (OR).

After the war, McNamara and other members of his office went to work at Ford Motor Company. Using these OR techniques, he achieved considerable success at the automobile company, ultimately rising to its top.[3] When McNamara was offered the job of Secretary of Treasury by the new Kennedy administration, it is reported that he replied he had more influence on interest rates at his current job as President of Ford. He later took a job as Secretary of Defense. Just a few months into his tenure, he ordered a major buildup of nuclear forces. This resolve came in spite of the fact that intelligence reports indicated that Soviet forces had been overestimated, the so-called “missile gap.”

McNamara was originally from Oakland, just a few miles northeast of the famed “Silicon Valley” and set out to transform US military strategy. In response to a RAND report that US bombers were vulnerable to a Communist first strike, he ordered the retirement of “most of the 1,292 old B-47 bombers and the 19 old B-58s, leaving ‘only’ 500 B-52s, to the surprise and anger of the Air Force.” He stopped production of the B-70 bomber that was estimated to cost $20 billion over the next ten years. Instead, he pushed the Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile project and continued to refine the notion of “massive retaliation” coined by Eisenhower’s Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in 1954.

The Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 seriously challenged this notion when the USSR began installing theatre-size SS-4, SS-5, and R-12 missiles on the Caribbean island in response to the deployment of US missiles in Turkey by the Eisenhower administration. When US surveillance revealed the missile sites, President Kennedy announced that any attack on the US from Cuba would be considered an attack by the USSR and would be responded to accordingly. He also ordered a blockade of the island nation, using the language of “quarantine” outlined by Roosevelt in 1937 in response to Nazi aggression.

On Oct 24, the Strategic Air Command elevated its alert status to Defense Condition 2 (DEF-CON 2), and as the USSR responded in kind, the world teetered on the brink of World War III. Last minute negotiations averted the catastrophe on October 28 when Premier Khrushchev agreed to remove their missiles from Cuba. Kennedy had offered in a secret deal to remove US missiles from Turkey. Perhaps not incidentally, the US Minuteman I program went operational on the same day.

The brains of the Minuteman I missile guidance system was the D-17B, a specialized computer designed by Autonetics. It contained an array of thousands of transistors, diodes, capacitors, and resistors designed to guide the warhead to its target. Guidance software was provided by TRW while the Strategic Air Command provided the actual targeting. Some 800 Minuteman-I missiles were manufactured and delivered by the time Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as President in 1965. As the Vietnam War increased tensions between the US and its Communist rivals, research was initiated on new models of the Minuteman missile. While the first Minuteman ICBM program used older transistors for its guidance systems, the later Minuteman II used integrated circuits (ICs) that continued to miniaturize the guidance and other intelligent aspects of the missile by reducing the number of electronic parts.[4]

Submarines carrying nuclear missiles became an extraordinarily lethal force using the new guidance technology. The first successful launch of a guided Polaris missile took place July 20, 1960 from a submerged George Washington class submarine. The USS George Washington was the first fleet ballistic missile submarine, carrying sixteen missiles. President John F. Kennedy came on board 16 November to observe a Polaris A1 launch. He subsequently ordered 40 more subs. These submarine-based missiles required even more sophisticated guidance technology because they had to be launched from one of a multitude of geographical positions. Submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) like the Poseidon and Trident eventually developed capabilities that could destroy entire countries.

McNamara started the buildup under Kennedy, but President Johnson urged him to keep up the missile program, arguing that it was the Eisenhower and Republicans who had left the US in weak military position. McNamara himself felt that nuclear missiles had no military purpose, except to “deter one’s opponent from using them,” but he pressed for their development.[1] The missiles required a complex guidance system, however, one that drew on the trajectory of the transistor and then integrated circuits research. As the military philosophy of “Mutually Assured Destruction” (MAD) emerged, the result was a prolonged support of the semiconductor industry leading ultimately to the information technologies of the computer and the Internet.

Minuteman-II production and deployment began with the Johnson administration as it embraced the “Assured Destruction” policy advocated by McNamara. The new model could go farther, pack more deadly force, and pinpoint its targets more accurately. Consequently, it could be aimed at more targets from its silos in the upper Midwest, primarily Missouri, Montana, Wyoming, as well as South and North Dakota. Nicknamed “MAD” for Mutually Assured Destruction, the policy recognized the colossal destructive capabilities of even a single thermonuclear warhead. A second strike could inflict serious damage on the attacker even if only a few warheads survived a first strike. Furthermore, the attempts at both a first and second strike could initiate a nuclear winter, bringing eventual destruction to the entire planet.

Consequently, the defensive strategy changed to building as many warheads as possible and putting them in a variety of positions, both fixed and mobile. Minuteman II production increased dramatically, providing a boost to the new IC technology and the companies that produced them. The D-37C computer installed in the missile was built in the mid-1960s using both the established transistor technology used in the first model as well as small scale integrated circuits recently introduced. Minuteman II consumption of ICs provided the incentive to create volume production lines needed for the 4,000 ICs needed weekly for the MAD missile deployment.[5]

The Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and Apollo space programs soon gave Silicon Valley a “liftoff,” as they required thousands of transistors and then integrated circuits. The transition occurred as NASA’s manned and satellite space program demanded the highest quality computing components for its spacecraft. It actively subsidized integrated circuits, a risky new technology where transistors were incorporated into a single wafer or “chip.” By the time Neil Armstrong first stepped on the Moon, more than a million ICs had been purchased by NASA alone.[6] These would become integral to the minicomputer revolution that rocked Wall Street and other industries in the late 1960s.

Citation APA (7th Edition)

Pennings, A.J. (2016, April 11). The MAD Origins of the Computer Age. apennings.com https://apennings.com/how-it-came-to-rule-the-world/the-mad-origins-of-the-computer-age/

Notes

[1] Robert McNamara quoted in Deborah Shapley’s (1993) Promise and Power: a Biography of the Secretary of Defense. published by Little, Brown and Company.

[2] Shapley, D. (1993) Promise and Power. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 108.

[3] Information on McNamara’s past from Paul Ewards, The Closed World.

[4] Information on Minuteman missiles provided by Dirk Hanson in The New Alchemists. p. 99.

[5] IC production lines from Ceruzzi, P.E. (2003) A History of Modern Computing. Second Edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 187.

[6] Reid, T.R., (2001) The Chip. NY: Random House. P. 150.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor at the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College in New York, and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor at the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College in New York, and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Tags: ARPA > AT&T > Cuban Missile Crisis > integrated circuits > intercontinental ballistic missile system (ICBM) > Jupiter C rocket > Minuteman intercontinental missile > Minuteman-II > Mutually Assured Destruction > operations research (OR) > Robert S. McNamara > Silicon Valley > transistors

Emerging Areas of Digital Media Expertise, Part 4: Business Acumen

Posted on | April 10, 2016 | No Comments

In previous posts, I discussed the importance of various skill sets in the emerging digital world: analytics and visualizations, design, global knowledge, technical, and the strategic communication aspects of digital media expertise.

The competitive world of digital activities requires proficiency in an extensive variety of marketing, graphic design, and digital production skills. The area of media management has emerged from broadcast media to embrace digital media, especially as the creative economy and its various manifestations: experience industries, cultural industries, and entertainment industries emerge as crucial parts of the global economy. In this post, I will discuss the centrality of commercial, entrepreneurial and management skills in today’s digital media environment.

Previously, those trained in media skills were primarily focused on the production of entertainment, educational, and cultural products and services. They were somewhat removed from business decisions unless they moved up to editorial or management positions later in their careers. With the transition to digital technologies and processes, business knowledge and media abilities are increasingly intertwined.

Some of the ways digital media production and business acumen overlap:

– Managing creative workers and digital innovation

– Assessing digital threats and opportunities

– Understanding global media and cultural trends

– Marketing content and producing multiple revenue streams

– Ensuring intellectual property rights and obtaining permissions

– Preparing digital content for local and global markets

– Working with diverse in-house and third party partners/vendors to construct working media-related applications

– Developing metrics for key performance, strategic, and management requirements

– Develop continuity plans in case of security, personnel, equipment or environmental failures

– Recruiting, managing and evaluating other key personnel

– Evaluating and implementing various e-payment solutions for both B2B and B2C operations

– Working with senior management and Board of Directors to establish current and long range goals, objectives, plans and policies

– Working with established creativity suppliers such as stars, independent producers, and agents

– Discerning how complex international legal environments influence intellectual property rights, consumer rights, privacy, and a various types of cybercrimes

– Manage remote projects and collaborate with colleagues and third party vendors via mediated conferencing

– Utilize project management skills and monitoring technologies such as Excel spreadsheets and methodologies such as SDLC waterfall, RAD, JAD, and Agile/Scrum

– Licensing and obtaining legal rights to merchandise and characters

– Assessing competitive advantages and barriers to entry

– Implement and monitor advertising and social media campaigns

– Anticipate the influence of macroeconomic events such as business cycles, inflation, as well as changes in interest rates and exchange rates on an organization’s sustainability

Leadership and management skills such as understanding how to facilitate teamwork among colleagues and third party partners/vendors to construct and commercialize working media-related applications are increasingly important. As enterprises and mission-based institutions flatten their organizational structures and streamline their work processes, fundamental knowledge about accounting, finance, logistics, marketing, and sales becomes more valuable.

Professional management certifications are a valuable qualification on contemporary resumes and represent valuable experience as well (4500 hours of project management work with a 4-year degree). Specific project management skills using Excel spreadsheets and the ability to monitor workflows using methodologies such as SDLC waterfall, RAD, JAD, and Agile/Scrum are also valuable to employers as are budgeting, change management, project control, risk assessment, scheduling, and vendor management. The ability to coordinate and manage remote projects with online teleconferencing and instant messaging capabilities is also crucial in a global environment to facilitate collaboration among colleagues, different business units and partnering B2B companies.

Last, but not least, sales expertise is in high demand in new media companies. Last year I was in San Francisco talking to a venture capitalist about needed skills and this category came up strongly. Sales success requires strong product knowledge, communication skills, planning abilities and self-management. Customer relations management has transformed sales management and with it modern retail and wholesale organizations. But just as significantly, customer expectations have risen to anticipate 24/7, global service from any point in the corporate operations.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College in New York, and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College in New York, and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Emerging Areas of Digital Media Expertise, Part 3: Global Knowledge and Geopolitical Risk

Posted on | March 5, 2016 | No Comments

This is the third post of a discussion on what kind of knowledge, skills, and abilities are needed for working in emerging digital media environments. It is recognized that students gravitate towards certain areas of expertise according to their interests and perceived aptitudes and strengths. In previous posts, I discussed Design, Technical, and Strategic Communication aspects and then later Analytics and Visualizations. Below I will examine an additional area:

Global knowledge is increasingly expected in work environments, especially those dealing with digital media and cultural industries that operate across ethnic, racial, and national borders. While this area is fluid due to rapid technological and political changes, knowledge of regions, individual countries, and subnational groupings are relevant. The globalization of media and cultural industries is very much a process of adjusting to local languages, aesthetic tastes, economic conditions (including currency exchange rates), and local consumer preferences.

The challenge of operating internationally presents significant risks of alienating customers, audiences, colleagues, and potential partners. Cultural differences in tolerances to risk avoidance, emotionalism, punctuality, ethnic differences, and formality could influence product acceptance, viewer habits, and workplace friction. The world of social media, in particular, contains significant potential risks for brand and reputation management. Unresolved cultural differences can lead to losses in efficiency, negotiations, and productivity when management strategy fails to account for cultural sensitivities in foreign contexts.

Assessing economic, health and political risks are also key to understanding the dynamics of foreign markets and operations. Economic factors such as exchange rate instability or currency inconvertibility, tax policy, government debt burden, interference by domestic politics and labor union strikes can influence the success of foreign operations. Extreme climate, biohazards, pollution and traffic dangers can threaten not only operations, but personnel as well.

Political risks from the violence of war or civil disturbances such as revolutions, insurrections, coup d’états, and terrorism should be assessed as well as corruption and kidnapping. Regulatory changes by host countries can influence media operations such as Russia’s recent requirement to store all data on Russian citizens within the country. Copyright and other intellectual property infringements are of particular concern to cultural and media industries.

Global knowledge often involves understanding how digital media and ICT can contribute to national development goals. Sustainable development objectives regarding education, health, sanitation, as well as energy and food production involving digital media have become high priorities in many countries. Knowing how indigenous and local communities can use these technologies for their specific goals and how performers and cultural practices can protect their intellectual property are high priorities. Gender justice and the empowerment women often rely on media to enhance social mobility and viability. Local governance involving infrastructure planning, social change, ethnic harmony may also involve technological components.

Digital services operating globally face trade-offs between projecting standardized features and customizing for local concerns. The latter involves cultural and emotional sensitivities as well as the ability to apply rational analysis to assess dangers to property, operational performance and most importantly, the people involved in foreign operations.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College in New York, and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College in New York, and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Digital Content Flow and Life Cycle: Global E-Commerce

Posted on | February 25, 2016 | No Comments

The term “e-commerce” provokes connotations of computer users “surfing” the web and using their credit cards to make online purchases. While this has been the popular conception, e-commerce continues to transform. The traditional model will continue to drive strong e-commerce sales for the retail sector, but other technologies and business models will also be important, especially with the proliferation of mobile and social technologies. E-commerce is as dynamic as the technologies and creative impulses involved and can be expected to morph and expand in concert with new innovations.

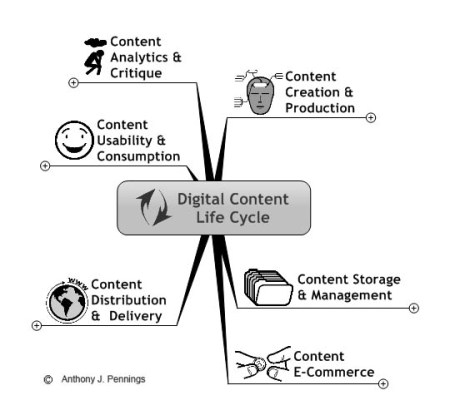

In this post, I will start to examine how e-commerce is a crucial stage in adding value to digital content. The graphic below represents the key steps in the digital media production cycle, starting at one o’clock.

The introduction of e-commerce into the media content life cycle is relatively new. I gave a talk to the Asian Business Forum in Singapore during the summer of 2000 that suggested broadcasters adopt an e-commerce model that included digitally serving, customizing, transacting, monetizing, interacting, delivering, and personalizing content.[1] I received quite a few blank stares at the time, maybe because it was a conference on “Broadcasting in the Internet Age.” Coming from New York City, I was familiar with the Silicon Alley discussions about the Internet and the changing media industries.

An analysis of the flow of digital content production can help companies determine the steps of web content globalization. A chain analysis involves diagramming then analyzing the various value-creating activities in the content production, storage, monetization, and distribution process. Furthermore, it involves an analysis of “informating” process, the stream of data that is produced in the content life cycle process. Digital content passes through a series of value-adding steps that prepare it for global deployment via data distribution channels to HDTV, mobile devices, and websites.[4]

Through this analysis, the major value-creating steps of content production and marketing process can be systematically identified and managed. In the graph above, core steps in digital production and linkages between them are identified in the context of advanced digital technologies. These are general representations but provide a framework to analyze the activities and flow of content production. Identifying these processes helps to understand the equipment, logistics, and skill sets involved in modern media production and also processes that lead to waste. In other posts I will discuss each of the following:

The Digital Value Chain

Content Creation and Production

Content Storage and Management

Content E-Commerce

Content Distribution and Delivery

Content Usability and Consumption

Content Analytics and Critique

Notes

[1] “Internet and Broadcasting: Friends or Foes?” Invited Presentation to the to the Asian Business Forum, July 07, 2000. Conference on Broadcasting in the Internet Age. Sheraton Towers, Singapore.

[2] Porter, Michael E. Competitive Advantage. 1985, Ch. 1, pp 11-15. The Free Press. New York.

[3] A version of this article appeared in the November–December 1995 issue of the Harvard Business Review.

[4] Singh, Nitish. Localization Strategies for Global E-Business.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College in New York, and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College in New York, and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Tags: e-commerce > global e-commerce > value chains

When Finance Went Digital

Posted on | February 5, 2016 | No Comments

By the end of the 1970s, a basic domestic and international data communications system was created that provided for the regime of digital monetarism to expand around the world. Drawing on ARPANET technologies, a set of standards emerged that was conducive to the public-switched telephony networks operated by the national telecom authorities such as France Telecom and Japan’s NTT (Nippon Telephone and Telegraph).

Rather than the user-oriented TCP/IP protocols that would take hold later, early packet-switched networking using a series of ITU technical recommendations emerged. The move was indicative of major tensions emerging between the governments that controlled international communications and the transnational commercial and financial institutions that wanted to operate globally. National telecommunications systems wanted to organize and control the networks with financial firms as their customers. They developed packet-switching protocols such as X.25 and X.75 for national and globally interconnected networks. Finance found their networks slow and wanted much more robust service that could give them competitive advantages and securer communications.

The increase in financial activity during the 1970s fed the demand for data communications and new computer technologies such as packet-switching networking, minicomputers, and “fail-safe” mainframes, such as Tandem Computers.

After the dissolution of the Bretton Woods Agreements, banks, and other financial businesses made it clear that new data services were needed for this changing monetary environment. They wanted computerized “online” capabilities and advanced telecommunications for participating in a variety of global activities including currency transactions, organizing syndicated loans, communicating with remote branches, as well as the complex data processing activities involved with managing ever-increasingly complex accounts and portfolios for clients.

For corporations, it meant computerized trading systems to manage their exposure in foreign currencies as they were forced, in effect, to become currency gamblers to protect their overseas revenues. Their activities required new information technologies to negotiate the complex new terrain brought on by the new volatility in international foreign exchange currency and the exponential rise in lending capital due to the syndicated Eurodollar markets.

The flood of OPEC money coming from the Oil Shocks increased the need for international data communications, as money in the post-Bretton Woods era was becoming increasingly electronic, and the glut of OPEC petrodollars needed a more complex infrastructure to recirculate its bounty to industrializing countries around the world.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College in New York, and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College in New York, and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Origins of Currency Futures and other Digital Derivatives

Posted on | January 13, 2016 | No Comments

Thus, it was fitting that Chicago emerged as the Risk Management Capital of the World—particularly since the 1972 introduction of financial futures at the International Monetary Market, the IMM, of the CME.

– Leo Melamed to the Council of Foreign Relations, June 2004

International currency exchange rates began to float in the post-Bretton Woods environment of the early 1970s. The volatility was created by US President Richard Nixon’s decision to end the dollar’s convertibility to gold and a new uncertainty produced in the international sphere, particularly by the two oil crises and the spread of “euro-dollars.”

Multinational corporations and other operations grew increasingly uneasy as prices for needed foreign monies fluctuated significantly. Those requiring another country’s money at a future date were unnerved by the news of geopolitical and economic events. Tensions in the Middle East, rising inflation, the U.S. military failure in Southeast Asia, were some of the major factors creating volatility and price variations in currency trading. This post introduces these new challenges to the global economy and how financial innovation tried to adapt to the changing conditions by creating a new system for trading currency derivatives.

Currency trading had long been a slow, glamour-less job in major banks around the world. Traders watched the telegraph, occasionally checked prices with another bank or two, and conducted relatively few trades each day. But with the end of the Bretton Woods controls on currency prices, a new class of foreign exchange techno-traders emerged in banks around the world. Armed with price and news information from their Reuters computer screens and with trading capabilities enhanced by data networks and satellite-assisted telephone services, they began placing arbitrage bets on the price movements of currencies around the world. Currency trading was transformed into an exciting profit center and career track. But the resulting price volatility raised concerns about additional risks associated with the future costs and availability of foreign currencies.

It was a condition that did not go unnoticed in Chicago, the historical center of US commodity trading. Members of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) in particular were curious if they could develop and trade contracts in currency futures. Enlisting the help of economist Milton Friedman, the traders at the CME lobbied Washington DC to allow them to break away from their usual trading fare and transform the financial markets. It helped that fellow and former University of Chicago professor George Schultz was the current Secretary of the Treasury.

In early 1972, the International Monetary Market (IMM) was created by the CME to provide futures contracts for six foreign currencies and start a new explosion of new financial products “derived” from base instruments like Eurodollars and Treasury bills.

The end of Bretton Woods also created the opportunity for a new “open outcry” exchange for trading in financial futures. The IMM was an offshoot of the famous exchange that preferred, initially, to distance themselves from “pork belly” trading and offer seats at a cheaper rate to ensure that many brokers would be trading in the pit. Growing slowly, at first, the IMM would be soon taken under the wing of the CME again and become the start of an explosion of derivative financial instruments that would soon grow into a multi-trillion dollar business.

The computer revolution would soon mean the end of “open outcry” trading strategies in the “pits” of the CME and the floors of other financial institutions like the NYSE. Open outcry is a system of trading whereby sellers and buyers of financial products aggressively make bids and offers in a face-to-face situation using hand signals. The system was preferably in trading pits because of deafening noise and the speed at which trading could occur. It also overcame crowd situations as traders could interact across a trading floor. But it lacked some of the flexibility and efficiencies that came with the computer.

In 1987, the members of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange voted for developing an all-electronic trading environment called GLOBEX, developed by the CME in partnership with Reuters. GLOBEX was designed as an automated global transaction system that was meant to replace eventually open outcry with a system of trading futures contracts that would not be limited to the regular business hours of the American time zones. They wanted an after-hours trading system that could be accessed in other cities around the world, and that meant trading 24/7.

Today’s $5.3 trillion dollars a day currency trading business is going through another transformation. Automation and electronic dealing are decimating foreign-exchange trading desks. Currency traders are now being replaced by computer algorithms.

Notes

[1] Leo Melamed, “CHICAGO AS A FINANCIAL CENTER IN THE TWENTY FIRST CENTURY,” A speech to the Council on Foreign Relations, Chicago, Illinois. June 2004.From http://www.leomelamed.com/Speeches/04-council.htm, accessed on November 14, 2004.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College, and Victoria University in New Zealand. During the 1990s he was also a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College, and Victoria University in New Zealand. During the 1990s he was also a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Tags: Bretton Woods > Chicago Mercantile Exchange > Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) > CME > eurodollars > IMM > International Monetary Market (IMM) > Milton Friedman

Statecraft and the First E-Commerce Administration

Posted on | January 7, 2016 | No Comments

One of techno-economic history’s most fascinating questions will deal with the stock market advances and technology developments during the 1990s. The eight years of the Clinton-Gore administration saw the proliferation of the Internet and telecommunications sectors. The Internet, a product of the Cold War, became a tool of global commerce.

The Presidential election of 1992 was notable for the phrase, “It’s the Economy Stupid” as Clinton attacked incumbent president George H. Bush for ignoring economic and social problems at home. The reigning president had a dramatic military victory with the “Desert Storm” military offensive that drove the Iraqis out of Kuwait, but years of federal budget deficits under the Republicans spelled his doom.

When the Clinton Administration moved into the White House in early 1993, the new administration was looking at budget deficits approaching a half a trillion dollars a year by 2000. Military spending and massive tax cuts of the 1980s had resulted in unprecedented government debt and yearly budget interest payments that exceeded US$185 billion in 1990, up substantially from the $52.5 billion a year when Ronald Reagan took office in 1982.[1] Reagan and Bush (like his son, George W.), while strong on national defense, never had the political courage to reduce government spending.

Clinton was forced to largely abandon his liberal social plans and create a new economic agenda that could operate more favorably within the dictates of global monetarism. This new trajectory meant creating a program to convince the Federal Reserve and bond traders that the new administration would reduce the budget deficit and lessen the government’s demand for capital.[2] Clinton made the economy the administration’s number one concern, even molding a National Economic Council in the image of famed National Security Council. Bob Rubin and others from Wall Street were brought in to lead the new administration’s economic policy. Clinton even impressed Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, who had grown weary of the Reagan legacy and what President Bush I had once called “voodoo economics.”[3]

Although the potential of the communications revolution was becoming apparent, what technology would constitute the “information highway” was not clear. Cable TV was growing quickly and offering new information services, while the Bell telephone companies were pushing Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN) and experimenting with ADSL and other copper-based transmission technologies. Wireless was also becoming a viable new communications option. But as the term “cyberspace” began to circulate as an index of the potential of the new technologies, it was “virtual reality” that still captured the imagination of the high-tech movement.

Enter the Web. Although email was starting to become popular, it was not until the mass distribution of the Mosaic browser that the Internet moved out of academia into the realm of the popular imagination and use. At that point the Clinton Administration would take advantage of rapidly advancing technologies to help transform the Internet and its World Wide Web into a vibrant engine of economic growth.

President Clinton tapped his technology-savvy running mate to lead this transformation, at first as a social revolution, and then a commercial one. Soon after taking office in early 1993, Clinton assigned responsibility for the nation’s scientific and technology affairs to Vice-President Gore.[3] Gore had been a legislative leader in the Senate for technology issues, channeling nearly $3 billion into the creation of the World Wide Web with the High Performance Computing Act of 1991, also known as the “Gore Bill.” While the main purpose of the Act was to connect supercomputers, it resulted in the development of a high bandwidth (at the time) network for carrying data, 3-D graphics, and simulations.[5] It also led to the development of the Mosaic browser, the precursor to Netscape and the Mozilla Firefox browsers. Perhaps, more importantly, it provided the vision of networked society open to all types of activities, including the eventual promise of electronic commerce.

Gore then shaped the Information and Technology Act of 1992 to ensure that Internet technology development would apply in public education and services, healthcare, and industry. Gore drove the National Information Infrastructure Act of 1993, that passed in the Congressional House in July of that year, but fizzled out due to a new mood to turn to the private sector for more direct infrastructure building. He turned his attention to the NREN (National Research and Education Network), which attracted attention throughout the US academic, library, publishing, and scientific communities. In 1996, Gore pressed the “Next Generation Internet” project. Gore had indeed “taken the initiative” to help create the Internet.

But the Internet was still not open to commercial activity. The National Science Foundation (NSF) nurtured the Internet during most of the 1980s. Still, its content remained strictly noncommercial by legislative decree, even though it contracted its transmission out to private operators. The Provisions in the NSF’s original legislation restricted commerce because of the “acceptable use policy” clause required in its funded projects.

But pressures began to mount on the NSF as it was becoming clear that the Internet was showing more commercial potential. Email use and file transfer were increasing dramatically. Also, the release of Gopher, a point-and-click way of navigating the ASCII files by the University of Minnesota, displayed textual information that could be readily accessed. Finally, Congressman Rick Boucher introduced an amendment to the National Science Act of 1950 that allowed commercial activities on the NSFNET.[6] A few months later, while waiting for Arkansas Governor William Jefferson Clinton to take over the Presidency, outgoing President George Bush, Sr. signed the Act into law. The era of Internet-enabled e-commerce had begun.

This is a good review of how the Internet and World Wide Web came to be.

Notes

[1] Debt information from Greider, W. (1997) One World, Ready or Not: The Manic Logic of Global Capitalism. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 308.

[2] Bob Woodward’s The Agenda investigated the changes the Clinton-Gore administration’s implemented after being extensively briefed on the economic situation they inherited. Woodward, B. (1994) The Agenda: Inside the Clinton White House. NY: Simon & Schuster.

[3] Information on Greenspan’s relationship with Clinton from Woodward, B. (1994) The Agenda: Inside the Clinton White House. NY: Simon & Schuster.

[4] Information on Gore’s contribution as Vice-President. Kahil, B. (1993) “Information Technology and Information Infrastructure,” in Branscomb, C. ed. Empowering Technology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

[5] Breslau, K. (1999) “The Gorecard,” WIRED. December, p. 321. Gore’s accomplishments are listed.

[6] Segeller, (1998) Nerds 2.0.1: A Brief History of the Internet

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College, and Victoria University in New Zealand. During the 1990s he was also a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College, and Victoria University in New Zealand. During the 1990s he was also a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Tags: Al Gore > National Science Foundation (NSF) > NSFNET > Rick Boucher

America’s Financial Futures History

Posted on | January 2, 2016 | No Comments

In his book, Nature’s Metropolis, (1991) William Cronen discussed the rise of Chicago as a central entrepot in the formation of American West. The city was strategically located between the western prairies and northern timberlands and with access routes by river and the Great Lakes. As a dynamic supplier of the nation’s food and lumber resources, Chicago was ideally suited to become the port city for the circulation of the West’s great natural bounty. Located on the shore of Lake Michigan, “Chicago stood in the borderland between the western prairies and eastern oak-history forests, and the lake gave it access to the white pines and other coniferous trees of the north woods. Grasslands and hardwoods and softwood forests were all within reach.”[1] With the westward expansion of agricultural settlements throughout the 19th century, farmers started to look for markets to sell their non-subsistence beef, pork, and wheat supplies. Likewise, they were attracted to the big city to buy northeastern industrial goods at lower prices.

By the 1880s, Chicago enthusiasts were soon making comparisons with Rome, noting however, that while “all roads lead to Rome;” Chicago would become “the Rome of the railroads.” The famous city got its start after 1833, when the local Indian tribes were forced to sign away the last of their legal rights to the area and the construction of the Erie Canal meant a new waterway to New York and the East Coast. It prospered through the Civil War where it played a key role in supplying the North with foodstuffs and other resources from the western frontier. Into the next century, Chicago would continue to grow into the central node of a vast trading network of nature’s bounty, what would generically be called “commodities.”

The “commodity” emerged as an abstract term to refer to items such as grains, meat products, and even metals that are bought and sold in a market environment. Commodities also came to be sold in “futures”, a legal contract specifying the change of ownership at a future time and at a set price. Bakeries in the East, for example, could lock in prices for future wheat deliveries. Key developments in the emergence of commodity trading were the notions of grading and interchangeability. To the extent that products could be separated into different qualities, they could be grouped together according to a set standard and they could then be sold anonymously.

While technological innovations such as the railroad and the steamship would dramatically increase the efficiency of transporting goods, the development of Chicago’s famed exchanges would facilitate their allocation. The Chicago Board of Trade was started in 1848 as a private organization to boost the commercial opportunities of the city, but would soon play a crucial part in the development of a centralized site for the Midwest’s earthly gifts. It was the Crimean War a few years later that spurred the necessity for such a commodities market. As the demand for wheat sales doubled and tripled, the CBOT prospered, and membership increased proportionally.

In 1856, the Chicago Board of Trade made the “momentous decision to designate three categories of wheat in the city – white winter wheat, red winter wheat, and spring wheat – and to set standards of quality for each.”[2] The significance of the action was that it separated ownership from a specific quantity of grain. As farmers brought their produce to the market, the elevator operator could mix it with similar grains and the owner could be given a certificate of ownership of an equal quantity of similarly graded grain. Instead of loading grain in individual sacks, it could be shipped in railroad cars and stored in silos. The grain elevators were a major technological development that increased Chicago’s efficiency in coordinating the movements and sales of its grains.

The Board was still having problems with farmers selling damp, dirty, low-quality and mixed grains, so it instituted additional variations. By 1860, the Chicago Board of Trade had more than ten distinctions for grain and its right to impose such standards was written into Illinois law making it a “quasi-judicial entity with substantial legal powers to regulate the city’s trade.”[3]

During this same time period, the telegraph was spreading its metallic tentacles throughout the country, providing speedy access to news and price information. The western end of the transcontinental link was built in 1861, connecting Chicago with cities like Des Moines, Omaha, Kearney, Fort Laramie, Salt Lake City, Carson City, Sacramento, and on to San Francisco.[4] The western link quickly expanded to other cities and connected Chicago with farmers, lumberjacks, prospectors and ranchers eager to bring their goods to market. News of western harvests often triggered major price changes as it was transmitted rapidly between cities. News of droughts, European battles, and grain shortages brought nearly instant price changes in Chicago. Newspapers were a major beneficiary of the electric links as they printed major news stories as well as price information coming over the telegraph. The telegraph quickly made the Chicago Board of Trade a major world center for grain sales and linked it with a network of cities such as Buffalo, Montreal, New York, and Oswego that facilitated the trade of grains and other commodities.

The telegraph also instituted the futures market in the US. As trust in the grade system sanctioned by the Chicago Board of Trade grew, confidence in the quality of the anonymous, interchangeable commodity also increased. The telegraph allowed for one of earliest e-commerce transactions to regularly occur. The “to arrive” contract specified the delivery of a specified amount of grain to a buyer, most often in an eastern city. The railroad and the steamboat made it easier to guarantee such a delivery and the guarantees also provided a needed source of cash for the Western farmers and their agents. These contracts could be used as collateral to borrow money from banks. While the “to arrive” contracts had seen moderate use previously, the telegraph (along with the grading system) accelerated their use. Along with the traditional market in grain elevator receipts, a new market in contracts for the future delivery of grain products emerged. Because they followed the basic rules of the Board, they could be traded. “This meant that futures contracts–like the elevator receipts on which they depended—were essentially interchangeable, and could be bought and sold quite independently of the physical grain that might or might not be moving through the city.”[5]

During the 1860s, the futures market became institutionalized at the Chicago Board of Trade. The Civil War helped facilitate Chicago’s futures markets as such commodities as oats and pork were in high demand by the Union Army. After the war, European immigration increased substantially in the eastern cities, further increasing the demand for western food and lumber commodities. Bakers and butchers needed a stable flow of ingredients and product. The new market for futures contracts transferred risk from those who could ill-afford it, the bread-bakers and cookie-makers, to those that wanted to speculate on those risks.

In 1871, Chicago suffered from a devastating fire, but the city came back stronger than ever. By 1875, the market for grain futures reached $2 billion, while the grain cash business was estimated at the lesser $200 million.[6] Abstract commodity exchange had surpassed the market of “real” goods. “To arrive” contracts facilitated by telegraph in combination with elevator receipts had made Chicago as the futures capital of the world.

In 1874, the precursor to the Chicago Mercantile Exchange was formed. Called the Chicago Produce Exchange, it focused on farm goods such as butter, eggs, and poultry. In 1919, at the end of World War I, the Chicago Produce Exchange changed its name to the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). It later expanded to trade frozen pork bellies as well as live hog and live pigs in the 1960s. The CME expanded yet again to include lean hogs and fluid milk, but its most important innovations came a decade later in the financial field.

Notes

[1] Quote on Chicago’s strategic location from Nature’s Metropolis, (1991) William Cronen, p. 25.

[2] Chicago Board of Trade’s momentous decision from William Cronen Nature’s Metropolis, (1991), p. 116.

[3] Additional information on the Chicago Board of Trade William Cronen Nature’s Metropolis, (1991), p. 118-119.

[4] Transcontinental link cities from Lewis Coe’s (1993) The Telegraph. London: McFarland & Co. p. 44.

[5] Quote on futures interchangeability from William Cronen Nature’s Metropolis, (1991), p. 125.

[6] Estimates of the grain and futures markets from William Cronen Nature’s Metropolis, (1991), p. 126.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College, and Victoria University in New Zealand. During the 1990s he was also a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea. Before joining SUNY, he taught at Hannam University in South Korea and from 2002-2012 was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, Marist College, and Victoria University in New Zealand. During the 1990s he was also a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Tags: Chicago Board of Trade > commodity > Erie Canal > Nature's Metropolis > William Cronen