Satellites for Global E-Finance and News

Posted on | May 17, 2025 | No Comments

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things — not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

– President John F. Kennedy, September, 1962 [1]

I found a chapter, “Satellites for Global E-Finance and News,” in my Document file for work I was doing on technology and the internationalization of money, particularly in the realms of finance and news. It traces the development and impact of satellite technology on international communications, primarily from the 1960s to the late 1980s. So I ran it through Google’s Gemini 2.5 AI and asked it to summarize. I edited it and posted it below.

The chapter demonstrates how satellite technology, driven by the demands of globalizing finance and the need for rapid news dissemination, navigated regulatory hurdles and technological advancements to become a crucial component of international communication infrastructure by the late 1980s. The chapter highlights the interplay between political decisions (deregulation), technological innovation (more powerful satellites, VSATs), and economic forces (the growth of global finance and media) in shaping this transformative period.

Inspired by John F. Kennedy’s vision of landing a man on the Moon and enabled by the space program and the Communications Act of 1962, Intelsat was formed, leading to the first global satellite communication system. Live broadcasts, especially the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, demonstrated its potential to the US and the world.

At the time, satellites had some significant advantages over undersea cables. They offered geography-insensitive connectivity, bypassing national terrestrial infrastructures and enabling point-to-point, point-to-multipoint, and broadcast transmissions. Fiber optic cables now provide much more capacity and speed, but satellites have become more sophisticated, especially new designs like SpaceX’s Starlink.

Satellites had a significant impact on the globalization of electronic finance. The end of the Bretton Woods agreement in the 1970s spurred the growth of electronic currency exchanges, which relied heavily on satellite data communication for financial news and transactions. The liberalization of the global financial and telecommunications regulatory environment allowed satellites to facilitate borderless commerce and e-money. This digital globalization led to the resurgence of the US dollar as the world’s reserve and trading currency.

Deregulation in the US helped propel new services. The 1972 Domestic Satellite Decision (“Open Skies”) was a crucial step in deregulating the US telecommunications system, allowing new companies to enter the satellite service market and setting a precedent for further deregulation. [2]

The Apollo space project spurred the development of stronger rockets and miniaturization of electronics, leading to larger and more sophisticated satellites like the Intelsat IVA with over 6,500 voice circuits and 2 TV channels by the mid-1970s (up from 240 voice circuits in Intelsat I). Satellites also began supporting packet-switched data communications thanks to the Alohanet and other networking projects.

Satellite communications became vital for electronic money and news flow. Cheaper long-distance telephone service, live broadcasting of major sports events, and faster news footage transmission from remote locations became possible. Newspapers like the Wall Street Journal saw significant benefits, reducing transmission costs from $3,500 per day to $90 and increasing plant productivity from 25,000 to 70,000 copies. Dow Jones’ revenues increased from $156 million in 1971 to $531 million ten years later.

Satellite technology facilitated the rise of global news networks like PBS (reaching 179 earth stations by 1984) and CNN (launched in 1980), enabling live, continuous news coverage from anywhere in the world. ABC’s Nightline exemplified this trend by its reporting on the Iranian hostage crisis and later the Tiananmen Square uprising in China. Hosted by Ted Koppel, the program conducted remote interviews with people such as UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutras Ghali. It combined the long distance service with some new studio technology and in the process developed a new form of news coverage that caught on quickly around the world.[3]

Europe also recognized the importance of space-based communications, forming the European Space Agency (ESA) in 1973 and developing the Ariane rocket, which became a primary launch vehicle, especially after the 1986 Challenger space shuttle disaster. I had a chance to visit the ESA’s European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) in Noordwijk, Netherlands in 1990 while visiting my uncle. It was while writing my PhD on electronic money and helped shape my thinking.

Satellite Business Systems (SBS) was formed by a joint venture between Aetna, Comsat, and IBM and aimed to provide high-speed data communications (45 megabits per second) for corporations. Despite technical capabilities (SBS-1 had a capacity for 1250 two-way telephone conversations per channel and 10 simultaneous color television transmissions with an average data rate of 480 megabits per second), SBS faced challenges due to the emergence of the X.25 protocol and the high cost of earth stations. It was eventually sold off.

Intelsat expanded rapidly, despite facing emerging competition. It launched its Intelsat V series in the mid-1980s, supporting both C-band and Ku-band frequencies and offering a wide range of services to 174 countries by 1987. Its International Business Services (IBS) catered to major international corporations.

In the early 1980s, the Reagan administration pushed for the deregulation of international satellite communications, challenging Intelsat’s monopoly. The FCC allowed new US International Service Carriers (USISCs) and open ownership of earth stations.

Deregulation also led to competition in launch vehicles. The NASA Space Shuttle program initially boosted the satellite industry by providing a reusable launch vehicle. However, the 1986 Challenger disaster led to a temporary halt and a shift towards privatization of launch services, allowing European (Ariane) and Chinese (Long March) rockets to gain market share.

Concerns arose regarding the limited resource of the geosynchronous orbit, conceptualized by Arthur C. Clarke. (see below) This shortage led to monitoring and regulation by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), primarily using a first-come, first-served principle, although political pressures for a registration system emerged.

Overall, “Chapter 12” “Satellites for Global E-Finance and News,”

explores how satellite technology evolved from the 1960s to the late 1980s to become a foundational infrastructure for global finance and news media. It illustrates the interaction between technological innovation, regulatory reform, and globalization, focusing on how satellites enabled real-time, transnational communication crucial for electronic money systems and financial journalism.

Citation APA (7th Edition)

Pennings, A.J. (2025, May 17) Satellites for Global E-Finance and News. apennings.com https://apennings.com/global-e-commerce/satellites-for-global-e-finance-and-news/

Notes

[1] Quote from JFK was from a speech given at Rice University in Houston Texas to dedicate NASA’s new Manned Spacecraft Center, 22 miles away.

[2] I always found Rob Frieden’s work on the FCC and international communications technology to be particulary useful. Parsons, P.R and Frieden, R.M. (1998) The Cable and Satellite Television Industries. Needham, MA: Allyn and Bacon. p. 52. Tim Logue, as well. Logue, Timothy “Recent Major U.S. Facilities-Related Policy Decisions: Letting a Million Circuits Bloom,” In Wedemeyer D. and Pennings, A. (eds.) Telecommunications-Asia, Americas, Pacific: PTC’ 86 Proceedings. p. 81.

[3] Hansen, Jarice. (1994) Connections: Technologies of Communication. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers. p. 162.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is a professor at the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea and a Research Professor for Stony Brook University. He teaches AI and broadband policy. From 2002-2012, he taught digital economics and information systems management at New York University. He also taught in the Digital Media MBA at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, where he lives when not in Korea.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is a professor at the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea and a Research Professor for Stony Brook University. He teaches AI and broadband policy. From 2002-2012, he taught digital economics and information systems management at New York University. He also taught in the Digital Media MBA at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, where he lives when not in Korea.

Tags: Domestic Satellite Decision > Nightline > Open Skies > SA's European Space Research and Technology Centre > SBS > US International Service Carriers (USISCs)

Determining Competitive Advantages for Tech Firms, Part 1

Posted on | May 14, 2025 | No Comments

Is the world more competitive for tech companies? Globalization has expanded market reach and access to talent, while the rapid pace of technological innovation constantly reshapes the competitive landscape. Lower barriers to entry have fostered a vibrant startup environment, challenging established players. The fierce competition for skilled technology talent further fuels this dynamic environment. Rising consumer expectations demand continuous improvements and innovations, and increasing regulatory scrutiny adds another layer of complexity. Finally, geopolitical factors significantly influence the global technology market and its supply chains. Working in concert, these forces have created a highly competitive arena where technology companies must constantly adapt and innovate to survive and thrive.

This post reworks one of two previous blogs that analyzed The Curse of the Mogul: What’s Wrong with the World’s Leading Media Companies by Jonathan A. Knee, Bruce C. Greenwald, and Ava Seave. I used it as part of the Digital Media Management curriculum at New York University and the Digital Media MBA at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas. It stresses the importance of substantial barriers to entry, or conversely, competitive advantages, for success in what economists call the “market structure” of a particular product.

The Curse of the Mogul emerged at a time when digital media firms were first starting to wrestle with the Internet. I draw on this book and other sources to continue to stress the importance of firms building strong barriers to entry in competitive economic environments. I changed the focus from digital media to tech companies in line with the changing vernacular and a shift in power to edge computing companies using AI and e-commerce.

The authors of Curse of the Mogul argue point out that companies should focus on developing and reinforcing more serious competitive advantages and/or operational efficiencies (disciplined management of resources, costs, and capital allocation).[1] They were critical of media mogul’s preoccupation with topics like brands, deep pockets, talent (creative, managerial), a global footprint, and first-mover benefits. These points are relevant but obscure other business factors that would likely facilitate better results.[2] Successful tech companies must define and protect more structural barriers to entry or adopt strict cost control procedures and operational efficiencies to enhance productivity and profitability.

Market structure has become a key focus of strategic thinking in modern firms. It refers to the environment for selling or buying a product or product series and influences key decisions about investments in production, people, and promotion. It is primarily about the state of competition for a product and how many rivals a company will have to deal with when introducing it. How easy is it to enter that market? Will the product be successful based on current designs and plans for it, or will the product need to be changed? How will the product be priced? Market structure is impacted by technological innovations, government regulations, network effects, customer behaviors, and costs.

Key factors include the number of firms supplying product, the level of differentiation between products offered, and the main focus of this post – the competitive advantages or barriers to entry that a company can erect to bolster their position or stave off competition. The pricing strategy can also be a factor but that is largely dependent on the level of competition.

In light of the rapid development and convergence of these tech and digitally-based industries, it is worth exploring the areas of key focus for the authors. In this post and the next, I review some of the major sources of competitive advantages according to The Curse of the Mogul and reference how they might apply to digital media firms. The book refers primarily to traditional big media firms. How do these categories of competitive advantage apply to a wider group of digital firms?[3] The authors distinguish four categories:

- Economies of scale and network effects;

- Customer captivity;

- Cost; and

- Government protection.[4]

Due to space constraints, I will cover economies of scale and customer captivity in this post and cost, innovation, and government protection in a future one.

Economies of Scale

This is a central concept in economics and refers to the benefits that come to a firm when it becomes more effcient. It may involve fixed costs or network effects. Fixed costs refer to both the traditional sense of decreasing costs per unit produced as well as to the barriers created by a company like Google with the ability to spend lavishly on equipment, knowledge attainment and other factors that make it prohibitive for other firms to match. Steven Levy’s “Secret of Googlenomics: Data-Fueled Recipe Brews Profitability” on the Wired website provides an excellent introduction to the search behemoth’s business model, primarily built around its Adwords and Adsense advertising business.

Google has a number of advantages, perhaps foremost being the massive investments in its built infrastructure. Google’s mission requires more than the most sophisticated “big data” software, it necessitates huge investments in physical plant, particularly data centers, power systems, cooling technologies, and high-speed fiber optic networks. Google has built up a significant global infrastructure of data centers (increasingly located close to cheap, green tech) and connecting its storage systems, servers, and routers is a network of fiber optic switches. For example, the Eemshaven data center facility in the Groningen region of the Netherlands is at the end connection point for a transatlantic fiber optic cable.

Large firms like Google can spread their fixed costs over greater volumes of production and operate more profitably than their competitors. For the most part, the details on fixed costs are not readily available as they are proprietary and represent trade secrets. However, aggregate numbers of Google’s fixed costs are informative.

Near Zero Marginal Costs

One of the characteristics of digital media is that although initial production costs may run high, the costs for additional viewers to experience the resulting digital content – movie, television show, software, song, or video game are negligible. Most digital goods can experience near-zero marginal costs. This advantage has been challenged in the age of Artificial Intelligence (AI) however, as the “compute” needed to produce results requires significantly more energy than traditional search.

Economies of scale for book publishers have always meant they needed to cover their fixed costs such as editors and author royalties before they can achieve profits. However, if they have a bestseller, it can be quite profitable as they spread their costs over a larger production run. Digital distribution through Amazon’s Kindle or Apple’s iBooks not only reduces the costs of production, but as no ink or paper is involved, it significantly reduces the costs of delivery as well. This happens for software as well. Microsoft Office, for example, which contains Access, Word, Excel, and PowerPoint, can be distributed over the Internet with little expense. But that is not necessarily a competitive advantage. Digital assets also need to be protected from copying and other forms of theft, and they need to utilize network effects and viral marketing.

Network Effects

Network effects refer to the increasing value of a product or service that occurs when additional customers or users start to use them. Many communications technologies such as telephones, fax machines, and text applications exhibit direct network effects. The telephone system became more valuable to each individual telephone subscriber as more people connected to the phone system. When more mobile phone users started to take advantage of Short Message Service (SMS) or “texting,” it attracted even more users. When I got my first text from my sister, for example, who was not known at the time for her technological prowess, I knew that texting had arrived.

Network effects are complicated and may not be sufficient and always be positive, as MySpace discovered after 2008 when members abandoned it for Facebook. MySpace was a social media site that allowed users to create their own “spaces” with pictures, blogs, music, and videos. The darling of early “social networking,” it was sold to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation for US$580 million dollars in 2005. Two years later, with 185 million registered users, it had a valuation of $65 billion. By early 2011 MySpace was down to about USD 63 million, while Facebook had jumped ahead with over 500 million members. Tired of pumping money into the sinking ship, News Corp. sold MySpace to Specific Media, an advertising network for $35 million, just 6% of its purchase price.[5] By 2025, Facebook had over 3 billion monthly active users (MAU).

Digital firms need to consider multiple repercussions such as cross-network and indirect network effects. The authors use the example of eBay, an online auction company that benefits from cross-network effects. eBay, Uber, Airbnb, and many other “platforms” such as dating or recruiting sites are also known as two-sided networks because they bring two distinct groups together. As the number of the eBay’s customers increased, it became increasingly attractive for others to sell their wares on the site. Conversely, as more products were displayed, it attracted more customers. A major success for Microsoft Office is that files produced on Word or Excel often need to shared and read by others.

Network effects makes a site or product more valuable as it includes more people and those additional people make it more attractive for another group. Credit cards, for example, are another good example of cross-network effects. They rely on a large base of individual card holders for profitability and this large customer base than attracts merchants who want their business and are willing to pay the extra costs to the credit card company. This raises questions about who you charge and if a proprietary platform is needed.

Over-the-top (OTT) services that use the Internet as a distribution system, like Amazon Prime, Netflix, and YouTube, connect consumers with content makers. While Prime and Netflix produce considerable content, they draw on outside content producers to keep their viewers engaged. YouTube has drawn heavily on user-generated content (UGC) as does Instagram and TikTok. In each case, the platform’s success depends on its direct network effects – its ability to connect a large number of viewers with a large number of producers.

Another phenomenon is indirect network effects. This occurs when the increasing use of one product or service increases the demand for complementary goods. The standardization of the Windows platform in the 1990s, for example, and its nearly ubiquitous installed user base among PC users allowed many other software producers to thrive as they built their applications to run on the Microsoft operating system. Both Apple and Android-based smartphones have allowed thousands of apps to be added to their functionality. So the network effects attributed to the popularity of these PCs and smartphones carry over to applications that run on them.

Viral Marketing

Viral marketing is a promotional strategy that relies on the audience to organically spread a marketing message to others, much like a biological virus. The goal is to create content that is so compelling, entertaining, or valuable that people will naturally want to share it with their friends, family, and colleagues. The key characteristics of viral marketing include rapid spread, user-driven growth, shareable content, and short-term growth.

Viral marketing’s primary aim is for the message to spread quickly and widely through social networks and word-of-mouth. Viral marketing relies on individuals to share the content, rather than the company paying for extensive distribution. Successful viral marketing campaigns typically involve content that evokes strong emotions, provides utility, or has a novelty factor that encourages sharing. While highly effective at generating initial awareness and a rapid influx of users, the effects of viral marketing can be short-lived if not coupled with other strategies. Examples of viral marketing campaigns include engaging videos, social media challenges like the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, and creative contests or giveaways.

Key Differences Between Network Effects and Viral Marketing

The main differences between network effects and viral marketing lie in their focus and the source of their power. The primary goal of network effects is to increase product/service value for users, while for viral marketing it is to achieve rapid user acquisition and brand awareness. The main mechanism for network effects is to increase value through the number of users while viral marketing works through the spread of shareable content created by the brand. The driver of network effects are the user connections and interactions. That also powers the sharing of content by individual users, which can feed more users for increased network effects. Network effects grows long-term sustainability and creates competitive advantage based on value production. Viral marketing creates rapid, short-term growth based on content appeal that can provide a temporary boost but doesn’t inherently build firm defensibility unless it results in more captured customers.[7]

Customer Captivity

Maintaining the attention and fealty of customers is often vital to a product’s success and is reinforced through habit, switching costs and search costs. Successfully introducing customer practices and reinforcing habitual use is a crucial strategy for retaining customers. Mobile apps lock users into a much more narrow range of options than surfing the Web on their PCs. Also, Amazon’s One-click purchase option makes it quick and easy to complete the deal without dragging out the credit card and inputting all the numbers and other information.

Speaking of credit cards though, they remain a consistent vehicle to keep a hold of customers through subscriptions and reward programs. Subscriptions use the automatic payments of credit cards to keep making the necessary payments to maintain the continous service or supply of product. Switching costs and reward forfeitures discourage giving up a credit card. Loyalty programs foster perceived value, not always real value. Switching mean may mean losing accumulated points, changing autopay for multiple bills, and potentially hurting one’s credit score due to new inquiries or shorter account history.

One new digital tool that is proving effective is the recommendation engine. Netflix uses a recommendation engine to keep customers engaged. It constantly suggests titles the viewer might be interested in watching based on their previous viewing. Amazon destroyed the Borders bookstore with its recommendation engine and an effective email system that targeted customers with what they wanted. Borders could only offer pictures of loosely associated books with dubious links to the customer’s interests. I, for example, was not interested in their fine collection of Harlequin-like romance novels. Borders did not recommend the books I wanted, so I bought them from Amazon, despite the enjoyment of going to the Borders bookstore.

It is also important to keep customers from switching to competitors. Switching barriers can involve exit fees, learning effort, equipment costs, emotional stress, start-up costs, as well as various types of risk: financial, psychological, and social. Cable and home security companies are notorious for trying to keep customers in long-term contracts to keep them from switching.

Making it easy to learn new products is helpful as is reducing any stresses associated with understanding new features or upgrading. One way to keep customers is to make the payment system easy. Automatic payments work for subscription-based services like Netflix and other deliverers of online content that tie in customers through credit cards and other continuous payment systems.

Search costs encourage consumers to stay with a particular product or entice them to go with your brand if the information provided is convincing enough to cause them to give up their search. Rational consumers will tend to search until the perceived benefits outweigh the costs. Testimonials and good reviews will help alleviate their concerns. Big ticket items like cars, homes, or major appliances tend to require more search time than smaller items. But any search requires a calculation of the opportunity costs involved. What are they giving up to spend this time searching?

In the passages above, I reviewed competitive advantages as specified by the authors of The Mogul’s Curse and applied them to digital media firms. Their focus on moguls doesn’t hold as much interest for me as their discussion about competitive advantages for smaller companies.[4] Being technologically dynamic, the digital media field is still investigating and exploring its ability to create competitive advantages and erect barriers to entry.

It is also important to understand that two or more competitive advantages may be operating at the same time. Recognizing the potential of reinforcing multiple barriers to entry and planning strategies that involve several competitive advantages will increase the odds for success. In “Determining Competitive Advantages for Tech Firms, Part 2,” I will discuss competitive advantages related to costs and government protection.

Review

This blog post summarizes key competitive advantages for firms, drawing from “Curse of the Mogul.” It emphasizes that success in a market’s structure depends on establishing strong barriers to entry or achieving operational efficiencies, rather than relying solely on brands, deep pockets, talent, global reach, or first-mover status. The post defines market structure and its influencing factors (technology, regulation, network effects, behavior, costs) and focuses on competitive advantages as barriers to entry. It then delves into several categories of competitive advantages.

Economies of scale and network effects are key barriers to entry. Firms can benefit from increased efficiency, including spreading fixed costs over larger production volumes (relevant for digital media with near-zero marginal costs, though AI compute challenges this with their high energy costs). Network effects are the increasing product/service value with more users (direct effects like communication technologies and indirect/cross-network effects seen in platforms like eBay, Uber, Airbnb, and the complementarity of products like Microsoft Office). The post notes that network effects aren’t always sustainable. For example MySpace vs. Facebook showed that network effects can tip one way or another quite fast. Once a platform reaches a critical mass of users, the value it offers becomes hard to replicate.

Customer captivity is reinforced through habitual use crucial for retention, as seen in mobile phone usage. Switching costs also present barriers preventing customers from moving to competitors and include fees, learning effort, equipment costs, and various risks. Also, search costs encourage sticking with an acquired product if the cost of searching start to outweigh the benefits of a new product. Recommendation engines and online reviews can play a role in reducing the costs of searching for a replacement product.

The post concludes by stating that the tech field is still exploring the creation of competitive advantages and barriers to entry. It highlights that multiple competitive advantages can operate simultaneously, increasing the likelihood of success.

Conclusion

This post outlines the critical importance of tech firms establishing powerful competitive advantages, particularly economies of scale, network effects, and customer captivity. These include firms operating in any market, including the dynamic digital media landscape. By dissecting these concepts and providing relevant examples from both traditional and digital companies, it underscores that sustainable success hinges on creating structural barriers to entry or achieving significant operational efficiencies, rather than relying on more superficial advantages often touted by industry leaders. The follow-up post on cost and government protection suggests a comprehensive exploration of the strategic levers available to companies seeking to thrive in competitive markets. Ultimately, the post serves as a framework for understanding how businesses can build lasting advantages in an ever-changing economic environment.

Citation APA (7th Edition)

Pennings, A.J. (2025, May 14). Determining Competitive Advantages for Tech Companies, Part I. apennings.com https://apennings.com/media-strategies/determining-competitive-advantages-for-digital-media-firms-part-1/

Notes

[1] Jonathan A. Knee, Bruce C. Greenwald, and Ava Seave, The Curse of the Mogul: What Wrong with the World’s Leading Media Companies. 2014.

[2] Knee, Greenwald, and Seave argue that the poor financial performance of major media conglomerates isn’t primarily due to external factors like the rise of the Internet. Instead, they contend that it stems from internal operational inefficiencies and misguided strategies driven by the egos and “megalomania” of media moguls. Lack of Focus on Cost Control: The moguls often prioritize growth, acquisitions, and maintaining a powerful image over rigorous cost management. They tend to downplay the importance of “number crunchers” and “pencil pushers,” leading to bloated budgets and unnecessary expenses. Driven by a desire for scale and market dominance, media companies frequently overpay for acquisitions and strategic investments that don’t yield commensurate returns. This misallocation of capital hinders profitability and shareholder value. Even when acquisitions have strategic rationale, poor integration processes often lead to duplicated efforts, loss of synergies, and ultimately, underperformance. The book challenges the notion that simply having the best content guarantees financial success. It argues that efficient distribution, marketing, and monetization strategies are equally, if not more, crucial. Moguls who fixate solely on content creation often neglect these operational aspects. Finally, the authors argued that moguls often believe their creative nature exempts them from standard financial scrutiny. This allows operational inefficiencies to persist without being adequately addressed. Unlike operationally efficient businesses that concentrate on core competencies and streamline processes, media conglomerates often lack focus, dabbling in diverse and sometimes unrelated ventures without achieving deep efficiencies in any one area.

[3]”Reviews: The_Curse_of_The_Mogul.” Quantum Media: Links_Reviews. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Mar. 2014.

[4] Greenwald, Bruce C. “The Moguls’ New Clothes.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, 01 Oct. 2009. Web. 30 Mar. 2014.

[5] Jackson, Nicholas. “As MySpace Sells for $35 Million, a History of the Network’s Valuation.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 29 June 2011.

[6] I finally found the hard copy of this book at a Borders near Wall Street in New York City.

[7] This post is a rewrite of the version I wrote in 2014. I used Gemini to add a more information on the distinction between network effects and viral marketing.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is a Professor at the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea, holding a joint research appointment at Stony Brook University. Before joining SUNY, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas. He was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is a Professor at the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea, holding a joint research appointment at Stony Brook University. Before joining SUNY, he taught at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas. He was on the faculty of New York University. Previously, he and Victoria University in New Zealand. He has also spent time as a Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Visual Rhetoric Analysis of Social Media: YouTube Channels and Memes

Posted on | May 1, 2025 | No Comments

What makes a successful YouTube channel? What meaning-making practices are used to make a channel interesting, or informative, or enjoyable? What story is being told, who is telling it, and how is it being told? How are people making money from it? These are some of the main questions we address in the final project of my EST 240 Visual Rhetoric and IT class. It examines the details of imagery or moving images closely for a rhetorical and denotation/connotative analysis of the persuasive techniques and meanings involved.

This post is about using a semiotic or visual rhetoric analysis to understand why some YouTube videos are successful, and others are not. Both rhetoric and semiotics offer valuable, yet distinct, frameworks for analyzing the complexities of visual media. While rhetoric, with its focus on the art of persuasion, examines the strategic use of appeals to ethos, pathos, and logos to influence audiences, semiotics delves into the science of signs, seeking to decode the underlying systems of meaning embedded within visual and auditory elements. Despite their different origins and primary objectives, these two disciplines share a fundamental concern with communication and meaning-making, particularly in our increasingly visually driven world.

The assignment is to interrogate a web channel, looking at its details, from its hosts to its thumbnails, to identify its signifying practices that make it a success. It may not be too different from an assignment to analyze a movie or a novel, as the meaning-making practices are examined much like a media paper. But YouTube is like a film on steroids, or a psychedelic drug. Its commitment to realism is lacking. A lot more is happening, and standard rules of organizing perception are being broken. Analyzing a YouTube channel takes a good eye for identifying details and a strong vocabulary to put what you see into words. It also requires an analytical framework to put the signifying practices into a theoretical perspective that helps create additional understanding of meanings created and the myths supported.

The class starts out with an intensive look at the vocabulary for techniques used in film, television, music videos, and more recently social media tools like Instagram, Rumble, Vine, TikTok. We move on to YouTube channels(with hosts for this assignment). Future versions of this course will also delve into the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to synthesize images and video.

Initially, we work on vocabulary and the “grammar” of visual creation – how moving images are shot and edited/structured to create meaning and narrative. We analyze films, television, music videos, and move on to YouTube videos. Terms like closeup, pan, tilt, parallel editing, and voice-overs provide key conceptual understanding for both technical and analytical purposes. Moving images are shot with a general grammar in mind – establishing shots for creating context, medium shots for introducing subjects and perspective, and closeups for detail and emotion.

I recommend analyzing the channel’s host first, drawing on the analysis of a newscaster or news “anchor.” The anchor secures the narrative of the news story. He or she (or AI it) literally anchors the meaning of the newscast or story. Stuart Hall talks about imagery needing a “fixed” meaning, which I find useful as well. The anchor or host tells a story, fixing the meaning but also moving the story along. What drives the “story” or myth-making? How is the story being told? Narration? Voiceover (VO)? Who is the author? Are they part of the story?

What is the rhetoric of the YouTube channel? What is the purpose of the site? What meanings does it produce? How does it engage the audience? What audience is it producing (How can it be sold to an advertiser?)

Two French terms have guided televisual analysis over the years: Mise-en-scène, for what is in the scene, or the shot. This is a combination of composition, costuming, hair and makeup, lighting, and set design. The other is Montage, from the French “to build,” that refers to the editing process. This action involves the pace of editing, wipes, continuity, and cross-cutting or parallel editing.

Recommended Outline

Introductions are drafted early but the last to be completed. Why is the channel a success? What metrics can we access to measure the success? How many subscribers does it have? How many videos have they produced? How many viewers do they attract? How many comments do they usually get? Can you find out how much money they are making? Dude Perfect has over 60 million subscribers and regularly makes over $20 million a year. It emphasizes male competition and sport. Genre is often an interesting exercise in the process of categorization that determines distinctions as well as similarities. A popular new genre on YouTube is the video blog or “vlog.”

Meaning-Creating Techniques 1 Denotation and Connotation: Host

Meaning-Creating Techniques 2 Denotation and Connotation: Shots (Mise en scène)

Meaning-Creating Techniques 3 Denotation and Connotation: Editing (Montage)

Additional areas of analysis:

Meaning-Creating Techniques 4 Denotation and Connotation: Logo

Meaning-Creating Techniques 5 Denotation and Connotation: Thumbnails

Rhetoric or Semiotics?

Despite their shared interests, rhetoric and semiotics exhibit fundamental differences in their historical development, primary objectives, and the specific analytical tools they employ. Rhetoric has its roots in the classical art of oratory, initially focusing on the principles of effective public speaking and argumentation. Semiotics, on the other hand, emerged later as a broader scientific and philosophical inquiry into the nature of signs and the processes by which meaning is generated and interpreted across all systems of communication, including film and YouTube. Ryan’s World is a particularly rich channel to analyze with almost 40 million subscribers and over 3000 videos.

Rhetoric’s primary concern lies with the persuasive intent behind communication and its impact on the audience’s beliefs or actions. Semiotics, however, has a more encompassing aim to understand the underlying structures and processes of signification, regardless of the communicator’s specific intentions or the message’s persuasive efficacy. Rhetoric traditionally emphasizes the appeals of logos, ethos, and pathos as its core analytical framework for examining persuasive strategies. In contrast, semiotics focuses on dissecting the structure of signs through concepts such as the signifier and signified, and the categorization of signs into icons, indices, and symbols. Furthermore, while rhetoric is primarily centered on human communication, semiotics has a broader scope. It extends its analysis to various phenomena that function as signs, including cultural rituals, fashion systems, and even biological communication among organisms (becoming more relevant with AI and big data’s capacity to capture and decipher animal sounds).

Analyzing Political Memes with Rhetorical Theory

Social media circulates many images with texts called “memes.” These constructions can be both effective and harmful as they can be constructed quickly with modern apps and spread virally through social media. Memes are often anonymous with little or no indication of authorship, yet are often shared from trusted friends.

Rhetoric can be used to analyze the techniques that are used to influence the reader. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle identified three fundamental modes of persuasion: ethos, pathos, and logos. These appeals form the cornerstone of rhetorical theory and provide a framework for analyzing how persuasion functions in communication, including visual media and memes.

Ethos is the appeal to credibility and centers on the character and trustworthiness of the communicator. In rhetoric, ethos is established by demonstrating expertise in the subject matter, conveying honesty and goodwill towards the audience, and presenting oneself with appropriate authority and character. For instance, in visual memes, the use of celebrity political endorsements leverages the perceived credibility and admiration associated with the celebrity to build trust in the policy. The audience is more likely to be persuaded by someone they view as knowledgeable, reputable, or possessing good political character. A political meme might showcase a political candidate in professional attire with a party logo.

Pathos is the appeal to emotion and involves persuading the audience by evoking certain feelings. These emotions can range from positive feelings like joy, hope, and excitement to negative ones such as sadness, fear, and anger. Visual media is particularly adept at employing pathos through the use of powerful imagery, evocative slogans, and compelling narratives designed to resonate with the audience’s values, beliefs, and cultural background. For example, a public service announcement might use distressing images to evoke empathy and encourage viewers to take action. A political meme might use patriotic imagery like the national flag to evoke pride.

Logos is the appeal to logic and relies on reason and evidence to persuade the audience. This involves using facts, statistics, logical arguments, and clear reasoning to support a particular claim or viewpoint. In visual rhetoric, logos can be conveyed through the presentation of data in infographics, demonstrations of a policy’s effectiveness, or a logical visual narrative that leads the viewer to a specific conclusion. A clear and specific thesis or claim, supported by well-reasoned arguments, is crucial for a strong appeal to logos. A political meme might include concise policy statements or slogans implying logical benefits.

The effective use of these three appeals, often in combination, is central to the art of rhetoric and its ability to influence audiences with memes quickly. Understanding how ethos, pathos, and logos are employed in visual media provides a valuable framework for analyzing the persuasive strategies at play in our visually saturated world.

Summary

This post underscores that success on YouTube is not just technical or algorithmic but rhetorical and semiotic. Content creators—whether kids unboxing toys or athletes competing—construct complex layers of meaning using visual tools and persuasive strategies. Understanding these tools equips students to critically analyze, produce, or even monetize content more effectively.

What makes a YouTube channel successful? The answer lies in metrics and how content is constructed, delivered, and interpreted. The post encourages a deep investigation of hosts, thumbnails, editing styles, and narrative strategies, using concepts like denotation/connotation, mise-en-scène, and montage — terms borrowed initially from film theory but now applicable to YouTube videos.

Citation APA (7th Edition)

Pennings, A.J. (2025, May 01) Visual Rhetoric Analysis of a YouTube Channel. apennings.com https://apennings.com/technologies-of-meaning/visual-rhetoric-analysis-of-a-youtube-channel/

Notes

[1] Rhetoric has an older lineage and appears to have started with a focus on persuasion and public speaking in ancient Greece. Semiotics, on the other hand, is a more recent and broader field that comes from linguistics and philosophy, looking at all kinds of signs, not just language. While rhetoric often has a goal of influencing people, semiotics is more about understanding how meaning works within different cultures.

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is a Professor at the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea and Research Professor at Stony Brook University. He teaches AI and broadband policy as well as visual rhetoric. Previously, he was on the faculty of New York University teaching digital economics and media management. He also taught in the Digital Media MBA at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, where he lives when not in Korea.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is a Professor at the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea and Research Professor at Stony Brook University. He teaches AI and broadband policy as well as visual rhetoric. Previously, he was on the faculty of New York University teaching digital economics and media management. He also taught in the Digital Media MBA at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, where he lives when not in Korea.

Tags: Chandler > connotation > denotation > Meaning-making practices > Memes > visual grammar > Visual Rhetoric and IT

Digital Disruption in the Film Industry – Part 4: Generative AI for Video Synthesis

Posted on | April 20, 2025 | No Comments

These are still the early days of artificial intelligence (AI) applied to video, but recently, the applications have rapidly accelerated, and enough has happened to comment. OpenAI’s SORA and Google’s Veo-2 are the current vanguards implementing extraordinary innovations in AI video applications but others such as Luma, Pika, and Runway are very competitive. How will these developments disrupt the current paradigm of media production and what does it mean for people wanting to use these new tools?

Generative AI for televisual video synthesis has become a major focus in my class EST 240 – Visual Rhetoric and Information Technologies. Although lectures have mainly focused on the signifying practices used in film, television, and YouTube channels, I am adding portions to cover AI techniques and prompt engineering required for effective AI generated media content. Connecting the vocabulary of televisual production to the possibilities of AI introduces students to new techniques that can enhance their careers.

This post introduces how AI is disrupting the media industry’s capacity to synthesize motion imagery. Generating video with AI requires not only creating visually plausible individual image frames but, crucially, form a coherent sequence with consistent objects, characters, environments, and logical motion over time. AI models achieve this by learning intricate patterns, relationships, and temporal dynamics from analyzing massive datasets containing existing video and image content.

AI can now take text prompts and generate full-motion video, thanks to a new class of computing models called text-to-video generative AI. These models interpret natural language descriptions and produce short video clips with varying levels of realism and coherence. These instruction sets guide the AI’s generation and synthesis of “tokens” – data points that are combined into the visual sequence through various algorithmic processes. Text prompts can be plugged into AI platforms like Runway, Pika Labs, or OpenAI’s Sora. They follow categories like these below.

Visuals: Earth modeled with digital/glowing textures

Focus: North and South America (you can add “seen from the western hemisphere”)

Grid Style: Spreadsheet-like structure wrapping or hovering around the globe

Mood: Futuristic, data-driven, cinematic

Motion: Rotating Earth, flickering grid lines, digital particles

Developing the rhetorical languages that can guide technical detail is important for harnessing the capabilities of generative AI. At a general level we use the French meaning-making concepts of Mise-en-scène and montage from film analysis to develop the understanding and language needed for visual prompts. More on that below after a brief scan of previous work in this series.

The Continuity of Disruption

For decades, AI primarily existed within the realm of science fiction cinema, often depicted as threatening humanity. 2001’s HAL 9000, The Terminator’s Skynet, and the machines of the Matrix series served as cautionary but fantastical tales. Now, AI has transitioned from a narrative trope into a tangible technological force actively reshaping modern moviemaking and continuing the mode of disruption that began with the introduction of microprocessing power in the film and video industries.

In my last post, I discussed the first examples of computer special effects (F/X) in movies such as Westworld (1973) and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982) based on NASA’s work with its Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) to develop an imaging system for Mariner 4, the Mars explorer. Digital F/X has continued with technology such as ILM’s Renderman, one of the first rendering software packages capable of using advanced rendering algorithms and shading techniques to create photorealistic images in CGI. Its allowed filmmakers to achieve lifelike lighting, textures, and reflections, enhancing the realism of digital environments and characters and winning numerous Oscar’s for Best Visual Effects.

AI-powered tools and software have transformed the field of visual effects (VFX) and animation, enabling filmmakers to create stunning, photorealistic CGI sequences and lifelike digital characters. AI algorithms can automate and streamline various aspects of the VFX production process, from rendering and compositing to motion capture and facial animation, saving time and resources while enhancing visual quality.

Before that, I posted on the transformation of post-production practices with the advent of Non-linear Editing (NLE) using AVID and other applications. I was there at the advent of the NLE revolution when the University of Hawaii was the first higher education institution to purchase an AVID NLE. I also used Clayton Christensen’s theory of innovative disruption to describe how digital editing progressed from very basic and almost crude computer applications and technology to the sophisticated, and now often very inexpensive techniques available on devices like smartphones, tablets, and PCs.

I started with how cameras had moved from film to digital, including a discussion on charge-coupled device (CCD) technology developed initially for spy satellites, and the development of cheaper and more energy-efficient complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology for digital cameras. The 4K resolution achieved by the Red One Camera rocked the film industry in 2007 and the same company’s Red Dragon 6K Sensor in 2013 have been extended into the company’s KOMODO and RAPTOR series.

Although useful in several stages of movie-making and promotion, the process of video synthesis is a cornerstone of its disruptive potential in filmmaking and has been progressing over time. Deepfake technology was the first form of video synthesis that captured the public’s attention when it used AI for face-swapping or recreating actors’ likenesses. Drawing on computer graphics, neural rendering has been used since 2020 in visual effects (VFX) to create realistic textures, lighting, and animations. AI-assisted editing included tools that automated scene cuts, color grading, or suggested improvements. Virtual production is a term that includes AI for real-time rendering, facial tracking, and scene generation. Synthetic media involves AI-generated visuals, dialogue, or characters for digital doubles or de-aged actors in movies such as Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019) as seen here.

Generative AI and Prompt Engineering for Video Synthesis

Generative AI such as Sora and New York City’s Runway is primarily focused on creating models and products for generating videos, images, and various multimedia content. AI is not a single, monolithic entity but rather a collection of rapidly changing technologies – including machine learning, natural language processing (NLP), computer vision, and sophisticated generative models – that are impacting nearly every facet of how films are conceived, created, and consumed. AI using machine learning algorithms and natural language processing, have been used to generate and analyze scripts, develop story ideas, and create entirely new digital content.

AI-driven systems also analyze vast amounts of data, including audience preferences, trends, and historical box office performance, to inform content creation decisions and even predict potential commercial success. The pace of change has accelerated dramatically in recent years, propelled by breakthroughs in generative AI, particularly diffusion models capable of creating increasingly realistic images and video sequences. These tools are increasingly available for use if you know how to access and guide them.

Notice the guidelines in this information about prompts from a dedicated YouTube channel.

Several platforms have emerged as leaders in the text-to-video and image-to-video generation space. Google’s Imagen Video and Veo, Meta’s Make-A-Video, Pika, Runway’s Gen-3, and Stable’s Diffusion Video currently have some of the most innovative models. These platforms introduce entirely new techniques for audiovisual content creation. This includes generating synthetic actors or digital doubles; creating photorealistic VFX elements like environments or specific effects such as explosions and intense weather; synthesizing video directly from text or images; generating dialogue or sound effects; and performing digital de-aging or applying digital makeup.

The process is pretty straightforward. At one level it follows the basic Turing computer model of input, processing, and output. You give a prompt like: “A dynamic 3D spreadsheet grid forms in space, encapsulating a glowing digital Earth. The Earth rotates slowly, with North and South America prominently displayed. The grid pulses with data streams and numbers, representing global analytics. Cinematic lighting with a futuristic blue and green palette, viewed from a slow-moving orbital camera.” Another level kicks in and AI processes the request using a multimodal transformer model trained on text and video data to interpret the scene from the text prompt. Then it outputs a short video (typically 2–20 seconds) showing that scene with motion, lighting, and camera movement.

Engines of Visual Generation

Conceptually, generative AI models are a class of AI systems specifically designed to create new, original data (text, images, audio, video, 3D models, etc.) that mimics the patterns and characteristics learned from their training data. Large Language Models (LLMs) like Chat GPT are particularly useful for researching and generating text that answer basic queries and research questions. Unlike discriminative models that classify or predict based on input, generative models learn the underlying distribution of the data to synthesize novel outputs. The process typically involves encoding the text prompt into a meaningful representation, (often using models like CLIP, a neural network that efficiently learns visual concepts from natural language supervision) which then conditions or guides the generative model (usually a diffusion model) during the video synthesis process.

Several core machine learning architectures and engines of visual generation underpin modern AI video generation. Key architectures enabling this include Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Diffusion Models, Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), as well as Transformers & RNNs (LSTMs). Each have specific strengths and weaknesses in generating different types of media.

GANs consist of two neural networks — a generator that creates synthetic data (images/video frames) and a discriminator that tries to distinguish between real and synthetic data. Through this adversarial process, the generator learns to produce increasingly realistic outputs. GANs are known for generating sharp, detailed images and can be relatively fast at generation once trained. However, they can be notoriously difficult to train stably and may suffer from “mode collapse,” where the generator produces only a limited variety of outputs. While used in some video synthesis approaches, they have been largely superseded by diffusion models for state-of-the-art results.

Diffusion models are a class of models has become dominant in high-quality image and video generation. The process involves two stages: first, gradually adding noise to training data over many steps until it becomes pure noise. Then, it trains a model (typically a U-Net architecture) to reverse this process, starting from noise and iteratively removing it (denoising) to generate a clean sample. Diffusion models generally produce higher-quality and more diverse outputs than GANs, often achieving superior realism. They also offer more stable training. A main drawback is the significantly slower generation speed due to the iterative denoising process, which can be thousands of times slower than GANs. Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs) address this partially by performing the diffusion process in a lower-dimensional “latent space” created by an encoder (like a VAE), making it more computationally efficient.

The Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) are generative models that have been repurposed for generative AI. They learn to encode data into a compressed latent representation and then decode it back. While they can generate images, these might sometimes be blurrier than GAN outputs. Their primary role in modern video synthesis is often as the encoder and decoder components within Latent Diffusion Models, enabling efficient processing in the latent space. They have also been explored for predicting motion in video generation and are used in generating image aspects.

Transformers and RNNs (LSTMs) include architectures that excel at processing sequential data. Transformers, particularly models like CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining), are crucial for understanding the relationship between text prompts and visual content, enabling effective text-to-image and text-to-video generation by guiding the diffusion process. Vision Transformer (ViT) blocks are often integrated within the U-Net architecture of diffusion models. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), such as LSTMs, have been used in earlier or alternative video generation models to help maintain temporal consistency across frames.

Temporal Consistency

The challenge of coherent motion is achieving temporal consistency – ensuring that objects, characters, lighting, and motion remain coherent and believable from one frame to the next throughout the video sequence. Without this, videos can appear jittery, nonsensical, or suffer from flickering artifacts. Diffusion models employ several techniques to address this critical hurdle for AI video generation. One is 3D U-Nets, architectures that extend the standard 2D U-Net used in image diffusion by incorporating a temporal dimension. Convolutions and attention mechanisms are factorized to operate across both space (within a frame) and time (across frames).

Another technique are temporal attention layers. These are specific layers added to the network architecture that allow different parts of a frame to “attend to” or share information with corresponding parts in other frames, explicitly modeling temporal relationships. Different attention strategies exist, such as attending to the same spatial location across all frames (temporal attention) or attending only to past frames (causal attention).

Frame interpolation is a video processing technique that creates new intermediating image frames between existing ones. It seeks to improve video quality by increasing the frame rate. Frame interpolation can be achieved through motion estimation that produces intermediate frames by calculating the motion vectors of pixels or blocks of pixels between frames and using them to predict the newly created frame. These vectors track the movement of pixels or blocks of pixels from one frame to the next and an algorithm predicts how objects in the video should move between the frames. By using these motion vectors, the algorithm can predict and generate new frames that follow the estimated motion paths.

A simpler approach blends the existing frames to create a new frame, although this can produce blurring or ghost effects. Also, morphing shapes objects from one frame to another and can be computationally intensive.

A related technique is hierarchical upsampling that uses text-to-video synthesis and operates like building a movie from a storyboard to provide high-resolution and temporally coherent video. It’s a core design principle in advanced generative models like Sora, Runway Gen-2, and Pika to scale from idea to realistic video. It starts with a sparse set of keyframes first and then uses the model (or simpler interpolation) to generate new and intermediating frames. It is easier to generate low-res previews and refines details. This progressively adds more frames per second to refine the spatial resolution while capturing the core semantics of the scene: motion, structure, general composition. Noise prediction and diffusion models are applied to enhance detail. These upsampling stages refine the spatial resolution and temporal consistency before investing in full computation for the final high-resolution (720p or 1080p at 24–30 fps) output with fine textures, lighting, shadows, and subtle motion.

Newer models like Sora aim to build more sophisticated internal representations of the world, including basic physics and object permanence, to generate more consistent and plausible motion and interactions. Despite progress, challenges remain. Maintaining high quality and consistency often becomes harder as the desired video length increases. Fine details, such as text legibility or the accurate depiction of complex objects like hands, can still be problematic, resulting in garbled or distorted outputs.

The quest for robust temporal consistency represents the next major frontier in AI video generation. While image generation models now produce stunningly realistic static visuals, the true utility of AI video in professional filmmaking hinges on its ability to create not just beautiful frames, but coherent, believable sequences. The techniques being developed—temporal attention, 3D architectures, world models—are direct responses to this fundamental challenge.

The qualitative difference between various AI video models often lies precisely in their capacity to handle motion, object persistence, and logical progression over time. Consequently, advancements in ensuring temporal coherence will be the primary driver determining how quickly and effectively AI video transitions from generating short, experimental clips to becoming a practical tool for longer-form narrative filmmaking. Overcoming current limitations, such as the occasional physics glitches or inconsistencies observed even in advanced models, is paramount. This area is where significant research, development, and competitive differentiation among AI platforms will likely occur in the near future.

That’s a Wrap!

As a continuation of my focus on disruption in the film industry, this post discusses the rapid advancements in AI-generated video and its growing impact on the media industry, particularly filmmaking. Generative AI models like Sora and Google Veo-2 are making significant strides in creating realistic and coherent video from user-initated text prompts. The post emphasizes the importance of teaching “prompt engineering” (crafting effective text instructions for AI) in media production courses, connecting it to traditional filmmaking concepts like mise-en-scène and montage.

A major hurdle in AI video generation is achieving temporal consistency, which means ensuring that objects, characters, and motion remain believable and coherent across video frames. It explains the workings of key AI architectures used in video synthesis, including GANs, Diffusion Models, VAEs, and Transformers. It highlights the dominance of Diffusion Models in achieving high-quality results. The post details specific techniques used to address the challenge of creating coherent motion, such as 3D U-Nets, temporal attention layers, frame interpolation, and hierarchical upsampling. The next major frontier in AI video generation is improving temporal consistency and overcoming limitations like inconsistencies and artifacts, especially in longer-form video.

In the meantime, many people can prepare for the opportunities inherent in AI-generated video production by developing their understanding and vocabulary of televisual production that they will need for effective prompting of desired moving image content.

Citation APA (7th Edition)

Pennings, A.J. (2025, Apr 20). Digital Disruption in the Film Industry – Part 4: Generative AI for Video Synthesis. apennings.com https://apennings.com/ditigal_destruction/digital-disruption-in-the-film-industry-part-4-generative-ai-for-video-synthesis/

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is a Professor at the Department of Technology, (AI), and Society, State University of New York, Korea teaching visual rhetoric and AI and broadband policy and holds a joint appointment as a Research Professor at Stony Brook Univeristy. From 2002-2012 he was on the faculty of New York University where he taught digital economics and media management. He also taught in the Digital Media MBA at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, where he lives when not in Korea.

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is a Professor at the Department of Technology, (AI), and Society, State University of New York, Korea teaching visual rhetoric and AI and broadband policy and holds a joint appointment as a Research Professor at Stony Brook Univeristy. From 2002-2012 he was on the faculty of New York University where he taught digital economics and media management. He also taught in the Digital Media MBA at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, where he lives when not in Korea.

Tags: Diffusion Models > Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) > generative AI > prompt engineering > text-to-video > Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

Moving Economic and Financial Curves

Posted on | March 9, 2025 | No Comments

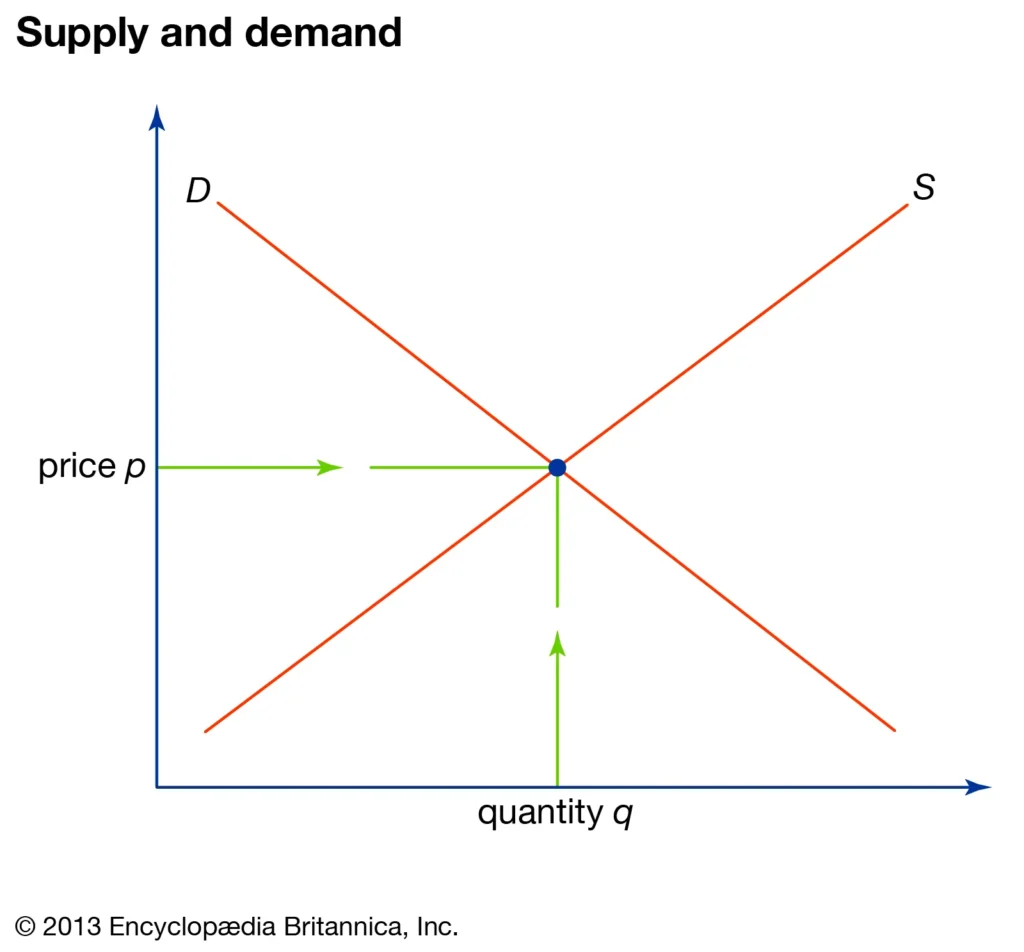

I’ve previously written about how the historical development of “one price” and equillibrium changed political economy to economics due to the development of market graphs. In these visualizations that empowered a new economics, supply and demand curves intersect at a “market clearing” price where suppliers and buyers of a good or service are happy to enact the transaction. This post lays out market logic and discusses what happens when changes in prices occurs, and when other factors might influence suppy and demand. The second part looks more closely at how supply and demand are both important and different in financial markets.

In financial markets, for example, the law of one price essentially states that identical or equivalent financial assets should trade at the same price, regardless of where they are traded. This is driven by the idea that if a discrepancy exists, arbitrageurs will exploit it, buying the asset where it’s cheaper and selling it where it’s more expensive, thus driving the price toward equality. If a company’s stock is traded on multiple exchanges, the law of one price suggests that its price should be the same across those exchanges (accounting for currency exchange rates, if applicable).

The equilibrium price is not static. It constantly adjusts based on shifts in supply and demand. If demand increases, the equilibrium price will likely rise, and vice versa. This post looks at factors that increase or decrease economic and financial curves.

Alfred Marshall, pictured below, made a valuable contribution to our understanding of supply and demand with his visible representation of the equillibrium price. Consequently, this framework provides a valuable graphical and mathematical foundation for understanding economic and financial market dynamics.

There are basic causes of a price change to be noted – shifts in demand (increase or decrease), supply (increase or decrease), or both

Although it’s important to distinguish between a “movement along” the demand curve (caused by a change in price), “shifts” of the demand curve can be caused by many other factors.

- Demand shifts to the right – An increase in demand shifts the demand curve to the right. This raises the price and output.

- Demand shifts to the left – A decrease in demand shifts the demand curve to the left. This reduces price and output.

- Supply shifts to the right – An increase in supply shifts the supply curve to the right. This reduces price and increases output.

- Supply shifts to the left – A decrease in supply shifts the supply curve to the left. This raises price but reduces output.

Factors That Shift the Demand Curve

– Income

For normal goods, an increase in income leads to an increase in demand (a rightward shift). For normal goods, a decrease in income leads to a decrease in demand (a leftward shift). For inferior goods (like generic brands), an increase in income leads to a decrease in demand, and vice versa.

– Prices of Related Goods

If the price of a substitute good increases, the demand for the original good increases (a rightward shift). If the price of a complementary good increases, the demand for the original good decreases (a leftward shift).

– Tastes and Preferences

Changes in consumer tastes and preferences, often influenced by advertising, trends, or cultural shifts, can significantly impact demand. Increased preference leads to increased demand (a rightward shift). Decreased preference leads to decreased demand (a leftward shift).

– Expectations

Consumer expectations about future prices, income, or availability can influence current demand. If consumers expect prices to rise in the future, current demand increases (a rightward shift). If consumers expect prices to fall in the future, current demand decreases (a leftward shift).

– Number of Buyers

An increase in the number of buyers in a market increases overall demand (a rightward shift). A decrease in the number of buyers decreases overall demand (a leftward shift).

– Demographic Changes

Changes in the size and composition of the population. For example a increase in the elderly population increases the demand for healthcare.

Accordingly, any factor that changes consumers’ willingness or ability to purchase a good or service at a given price will cause the demand curve to shift.

In market graphs, the supply curve illustrates the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity that producers are willing to supply. Once again, it’s important to differentiate between a “movement along” the supply curve (caused by a change in price) and a “shift” of the supply curve (caused by other factors).

Factors That Shift the Supply Curve

– Costs of Production

Changes in the prices of inputs, such as labor, raw materials, and energy, directly affect the cost of production. Increased costs shift the supply curve to the left (a decrease in supply). Decreased costs shift the supply curve to the right (an increase in supply).

– Technology

Technological advancements can improve production efficiency, reducing costs and increasing output. New technology generally shifts the supply curve to the right.

– Government Policies

Taxes on production increase costs, shifting the supply curve to the left. Subsidies reduce production costs, shifting the supply curve to the right. Regulations can increase or decrease production costs, depending on their nature, and therefore shift the supply curve accordingly.

– Number of Sellers

An increase in the number of sellers in a market increases the overall supply, shifting the curve to the right.

A decrease in the number of sellers decreases supply, shifting the curve to the left.

– Expectations of Future Prices

If producers expect prices to rise in the future, they may reduce current supply to sell more later, shifting the curve to the left.

If they expect prices to fall, they may increase current supply, shifting the curve to the right.

– Prices of Related Goods

If the price of a related good that producers could also produce increases, they may shift production towards that good, decreasing the supply of the original good (shifting the supply curve to the left).

– Natural Disasters

Natural disasters can heavily effect the amount of goods that can be produced. Therefore these events can cause massive shifts in the supply curve.

Basically, any factor that changes the producers’ ability or willingness to supply a good or service at a given price will cause the supply curve to shift.

What Factors Change Demand and Supply Curves in Financial Markets?

In financial markets, like any other market, the interplay of supply and demand determines prices. However, the factors that shift these curves have some unique characteristics.

Factors Affecting Demand in Financial Markets

– Interest Rates

When interest rates fall, borrowing becomes cheaper, increasing the demand for loans and other debt instruments. Conversely, higher interest rates reduce borrowing and can increase the demand for interest-bearing assets like bonds.

– Investor Sentiment

Optimism about the economy or a particular asset can increase demand. Fear and uncertainty can lead to a decrease in demand, as investors seek safer havens.

– Economic Data

Strong economic indicators, like GDP growth or low unemployment, can increase demand for stocks and other risk assets. Weak economic data can have the opposite effect.

– Inflation Expectations

Rising inflation expectations can decrease demand for bonds, as their real return erodes.

Conversely, it can increase demand for assets that are expected to outpace inflation, like commodities or certain stocks.

– Government Policies

Fiscal policies, like tax cuts or increased government spending, can stimulate demand. Monetary policies, like changes in the money supply, can also influence demand.

– Changes in Risk Aversion

When investors risk aversion is low, they are more willing to purchase riskier assets, increasing demand. When risk aversion is high, demand shifts to safer assets.

Factors Affecting Supply in Financial Markets

– Central Bank Policies

Central banks influence the supply of money through open market operations, reserve requirements, and the discount rate. These actions directly impact the supply of credit and other financial instruments.

– Corporate Issuances

Companies issue stocks and bonds to raise capital, increasing the supply of these instruments.

The number of corporate issuances depends on factors like economic conditions and interest rates.

– Government Issuances

Governments issue bonds to finance their spending, adding to the supply of debt instruments.

– Investor Expectations

If investors expect the price of an asset to fall, they may increase their supply of that asset in order to sell before the price drops.

– Profitability Expectations

If a company is expecting high profitability, they may issue more stock, increasing supply.

Key Differences from Traditional Goods Markets

In reality, frictions in financial markets like transaction costs, taxes, and information asymmetries can prevent the law of one price from holding perfectly. Also, the degree to which the law of one price holds depends on the efficiency of the market. In highly efficient markets, price discrepancies are quickly eliminated. Lastly, some financial instruments are highly complex, making it difficult to determine whether they are truly identical.

In financial markets, expectations play a much larger role than in markets for physical goods. Information flows very rapidly, leading to quick adjustments in supply and demand. Psychological factors, like fear and greed, also have a significant impact on market dynamics.

Citation APA (7th Edition)

Pennings, A.J. (2025, March 10) Moving Economic and Financial Curves. apennings.com https://apennings.com/dystopian-economies/moving-the-curves-to-achieve-equillbrium-prices/

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Anthony J. Pennings, PhD is a professor at the Department of Technology and Society, State University of New York, Korea and holds a joint position as a Research Professor for Stony Brook University. He teaches policy and ICT for sustainable development. From 2002-2012 he taught digital economics and information systems management at New York University. He also taught in the Digital Media MBA at St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, where he lives when not in the Republic of Korea.